Lojban is a logical language: the name of the language itself means “logical language”. The fundamentals of ordinary logic (there are variant logics, which aren't addressed in this book) include the notions of a “sentence” (sometimes called a “statement” or “proposition”), which asserts a truth or falsehood, and a small set of “truth functions” , which combine two sentences to create a new sentence. The truth functions have the special characteristic that the truth value (that is, the truth or falsehood) of the results depends only on the truth value of the component sentences. For example,

is true if “John is a man” is true, or if “James is a woman” is true. If we know whether John is a man, and we know whether James is a woman, we know whether “John is a man or James is a woman” is true, provided we know the meaning of “or”. Here “John is a man” and “James is a woman” are the component sentences.

We will use the phrase “negating a sentence” to mean changing its truth value. An English sentence may always be negated by prefixing “It is false that ...” , or more idiomatically by inserting “not” at the right point, generally before the verb. “James is not a woman” is the negation of “James is a woman” , and vice versa. Recent slang can also negate a sentence by following it with the exclamation “Not!”

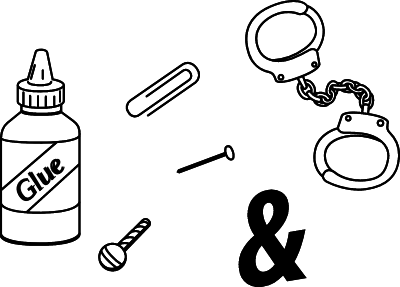

Words like “or” are called “logical connectives” , and Lojban has many of them, as befits a logical language. This chapter is mostly concerned with explaining the forms and uses of the Lojban logical connectives. There are a number of other logical connectives in English such as “and” , “and/or” , “if” , “only if” , “whether or not” , and others; however, not every use of these English words corresponds to a logical connective. This point will be made clear in particular cases as needed. The other English meanings are supported by different Lojban connective constructs.

The Lojban connectives form a system (as the title of this chapter suggests), regular and predictable, whereas natural-language connectives are rather less systematic and therefore less predictable.

There exist 16 possible different truth functions. A truth table is a graphical device for specifying a truth function, making it clear what the value of the truth function is for every possible value of the component sentences. Here is a truth table for “or” :

| first | second | result |

| True | True | True |

| True | False | True |

| False | True | True |

| False | False | False |

This table means that if the first sentence stated is true, and the second sentence stated is true, then the result of the truth function is also true. The same is true for every other possible combination of truth values except the one where both the first and the second sentences are false, in which case the truth value of the result is also false.

Suppose that “John is a man” is true (and “John is not a man” is false), and that “James is a woman” is false (and “James is not a woman” is true). Then the truth table tells us that

| “John is a man, or James is not a woman” (true true ) is true |

| “John is a man, or James is a woman” (true , false) is true |

| “John is not a man, or James is not a woman” (false, true ) is true |

| “John is not a man, or James is a woman” (false, false) is false |

Note that the kind of “or” used in this example can also be expressed (in formal English) with “and/or”. There is a different truth table for the kind of “or” that means “either ... or ... but not both”.

To save space, we will write truth tables in a shorter format henceforth. Let the letters T and F stand for True and False. The rows will always be given in the order shown above: TT, TF, FT, FF for the two sentences. Then it is only necessary to give the four letters from the result column, which can be written TTTF, as can be seen by reading down the third column of the table above. So TTTF is the abbreviated truth table for the “or” truth function. Here are the 16 possible truth functions, with an English version of what it means to assert that each function is, in fact, true ( “first” refers to the first sentence, and “second” to the second sentence):

| TTTT | (always true) |

| TTTF | first is true and/or second is true. |

| TTFT | first is true if second is true. |

| TTFF | first is true whether or not second is true. |

| TFTT | first is true only if second is true. |

| TFTF | whether or not first is true, second is true. |

| TFFT | first is true if and only if second is true. |

| TFFF | first is true and second is true |

| FTTT | first and second are not both true. |

| FTTF | first or second is true, but not both. |

| FTFT | whether or not first is true, second is false. |

| FTFF | first is true, but second is false. |

| FFTT | first is false whether or not second is true. |

| FFTF | first is false, but second is true. |

| FFFT | neither first nor second is true. |

| FFFF | (always false) |

Skeptics may work out the detailed truth tables for themselves.