The following cmavo are discussed in this section:

|

poi |

NOI |

restrictive relative clause introducer |

|

ke'a |

GOhA |

relative pro-sumti |

|

ku'o |

KUhO |

relative clause terminator |

Let us think about the problem of communicating what it is that we are pointing at when we are pointing at something. In Lojban, we can refer to what we are pointing at by using the pro-sumti ti if it is nearby, or ta if it is somewhat further away, or tu if it is distant. (Pro-sumti are explained in full in Chapter 7.)

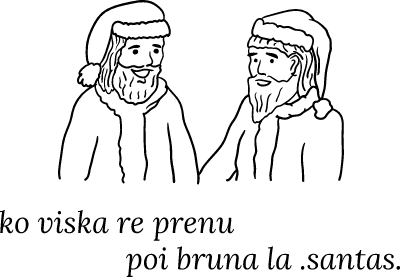

However, even with the assistance of a pointing finger, or pointing lips, or whatever may be appropriate in the local culture, it is often hard for a listener to tell just what is being pointed at. Suppose one is pointing at a person (in particular, in the direction of his or her face), and says:

What is the referent of ti ? Is it the person? Or perhaps it is the person's nose? Or even (for ti can be plural as well as singular, and mean “these ones” as well as “this one”) the pores on the person's nose?

To help solve this problem, Lojban uses a construction called a “relative clause”. Relative clauses are usually attached to the end of sumti, but there are other places where they can go as well, as explained later in this chapter. A relative clause begins with a word of selma'o NOI, and ends with the elidable terminator ku'o (of selma'o KUhO). As you might suppose, noi is a cmavo of selma'o NOI; however, first we will discuss the cmavo poi , which also belongs to selma'o NOI.

In between the poi and the ku'o appears a full bridi, with the same syntax as any other bridi. Anywhere within the bridi of a relative clause, the pro-sumti ke'a (of selma'o KOhA) may be used, and it stands for the sumti to which the relative clause is attached (called the “relativized sumti”). Here are some examples before we go any further:

| ti | poi | ke'a | prenu | ku'o | cu | barda |

| This-thing | such-that-( | IT | is-a-person | ) | is-large. |

|

This thing which is a person is big. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This person is big. |

| ti | poi | ke'a | nazbi | ku'o | cu | barda |

| This-thing | such-that-( | IT | is-a-nose | ) | is-large. |

|

This thing which is a nose is big. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This nose is big. |

| ti | poi | ke'a | nazbi | kapkevna | ku'o | cu | barda | |

| This-thing | such-that-( | IT | is-a-nose | type-of | skin-hole | ) | is-big. |

|

These things which are nose-pores are big. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These nose-pores are big. |

In the literal translations throughout this chapter, the word “IT” , capitalized, is used to represent the cmavo ke'a. In each case, it serves to represent the sumti (in Example 8.2 through Example 8.4 , the cmavo ti) to which the relative clause is attached.

Of course, there is no reason why ke'a needs to appear in the x1 place of a relative clause bridi; it can appear in any place, or indeed even in a sub-bridi within the relative clause bridi. Here are two more examples:

| tu | poi | le | mlatu | pu | lacpu | ke'a | ku'o | cu | ratcu |

| That-distant-thing | such-that-( | the | cat | [past] | drags | IT | ) | is-a-rat. |

|

That thing which the cat dragged is a rat. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What the cat dragged is a rat. |

| ta | poi | mi | djica | le | nu |

| That-thing | such-that-( | I | desire | the | event-of( |

| mi | ponse | ke'a | [kei] | ku'o | cu | bloti |

| I | own | IT | ) | ) | is-a-boat. |

|

That thing that I want to own is a boat. |

In Example 8.6 , ke'a appears in an abstraction clause (abstractions are explained in Chapter 11) within a relative clause.

Like any sumti, ke'a can be omitted. The usual presumption in that case is that it then falls into the x1 place:

almost certainly means the same thing as Example 8.3. However, ke'a can be omitted if it is clear to the listener that it belongs in some place other than x1:

is equivalent to Example 8.4.

As stated before, ku'o is an elidable terminator, and in fact it is almost always elidable. Throughout the rest of this chapter, ku'o will not be written in any of the examples unless it is absolutely required: thus, Example 8.2 can be written:

without any change in meaning. Note that poi is translated “which” rather than “such-that” when ke'a has been omitted from the x1 place of the relative clause bridi. The word “which” is used in English to introduce English relative clauses: other words that can be used are “who” and “that” , as in:

and

In Example 8.10 the relative clause is “who was going to the store” , and in Example 8.11 it is “that the school was located in”. Sometimes “who” , “which” , and “that” are used in literal translations in this chapter in order to make them read more smoothly.